Changing the Focus, Making Thinking Visible

How can art help students better understand how they think and process information?

By Dana Squires

Art is not a set of skills. Art is a process-oriented winding path of observation, questioning, and exploration.

This is one reason why incorporating art into other curriculum subjects is so powerful. Art teaches us to see and reflect on ideas in different ways, from different angles and approaches.

When creating art in the classroom, the end product is most often the focus. But as teachers, we forget the learning that happens somewhere on the journey. This learning goes far beyond how to hold a paintbrush or that mixing yellow and blue make green.

By shifting our focus and attention to the brief insightful moments of seeing, critical thinking, and creative problem-solving rather than the finished product, we can reinforce creative thinking, synthesizing and evaluating information, and raise the awareness of the learning that is taking place. Students become thinkers.

Making Thinking Visible in action:

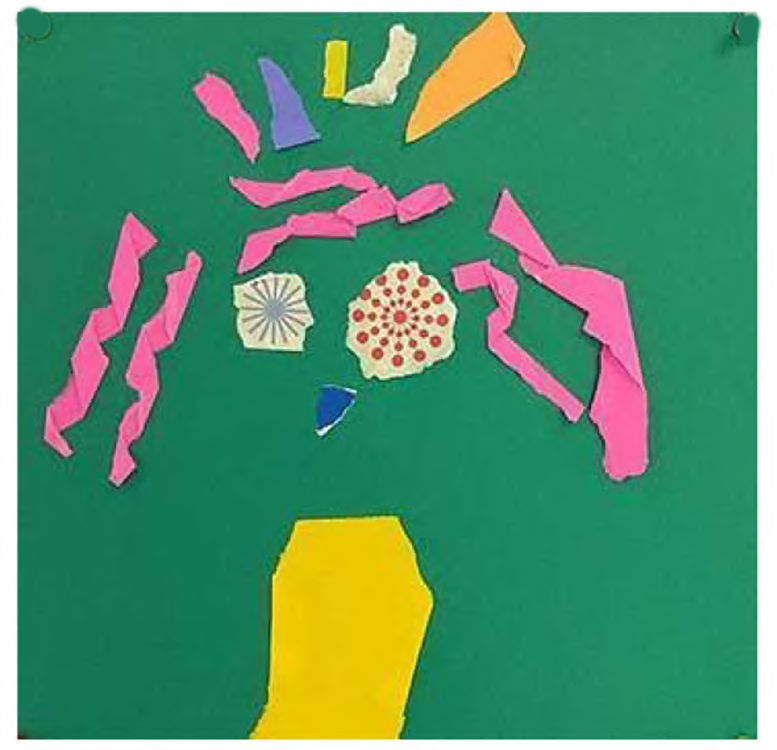

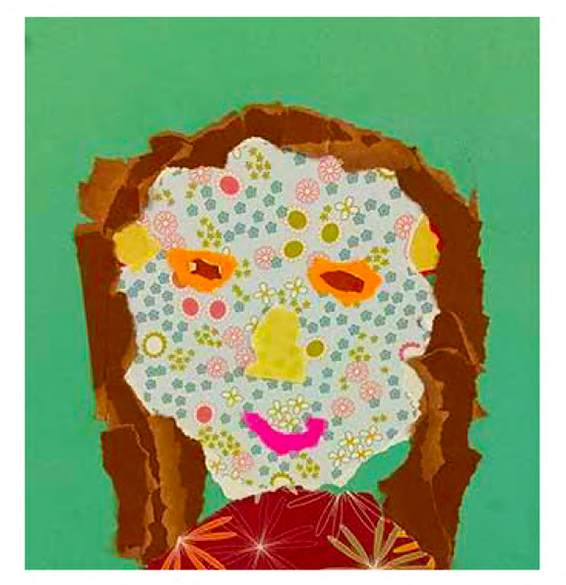

In my classes, one way I focus on making thinking visible is to frame projects in terms of questions to solve rather than an outcome. For example, I often do a self-portrait project at the beginning of the year. The idea is not to have a representational picture, but to give students the opportunity to explore who they are. After we define “self-portrait” – basically a picture of oneself – I give students a variety of fun and brightly colored and printed papers (origami paper is great) and ask them to make a self-portrait by tearing the paper and gluing it on the page.

Since none of the students have green faces, and tearing paper is less than precise, the question shifts from “What do I look like (and how do I draw that?)” to “How do I make a self-portrait that looks like me using these materials?”

The answer is you can’t.

The question needs to be even broader.

The assignment becomes: Create a self-portrait that shows something about who you are, not what you look like.

It is not about creating a “perfect” portrait or being able to make a realistic drawing. The question is now “What makes you YOU?” I am always amazed at the insightful things students come up with. And how expressive torn paper can be.

A note about using torn paper rather than drawing/painting or even the use of scissors: Tearing paper removes skill from the equation and levels the playing field for their self expression. Students who “can’t draw” can tear paper along with the best of them and it is not just the “artists” in the room that are successful. With only torn paper and a glue stick the performance anxiety and expectation is low, and that allows real creativity to shine through.

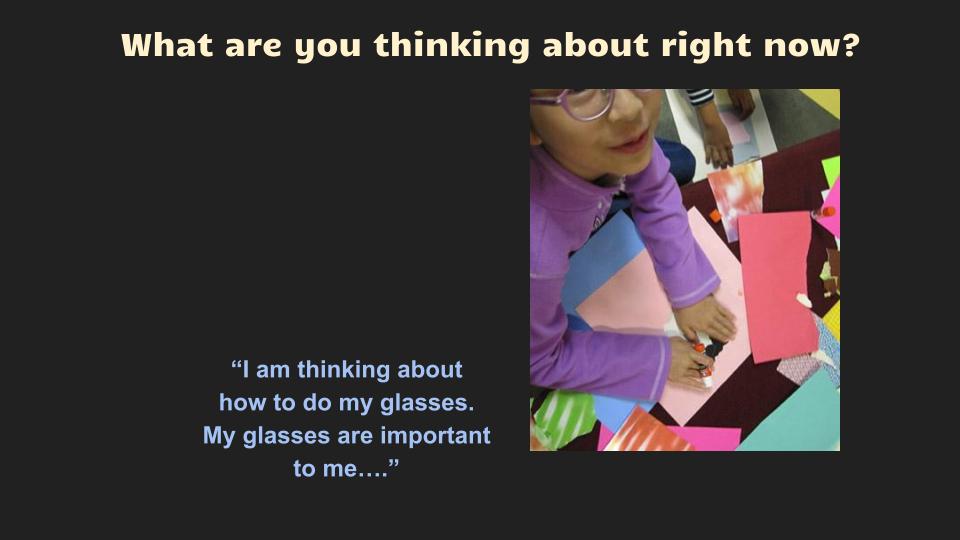

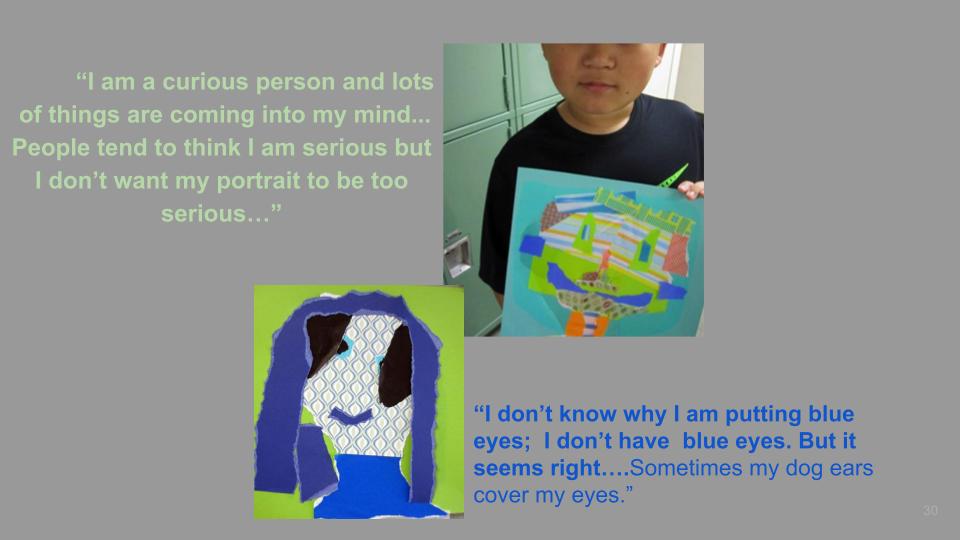

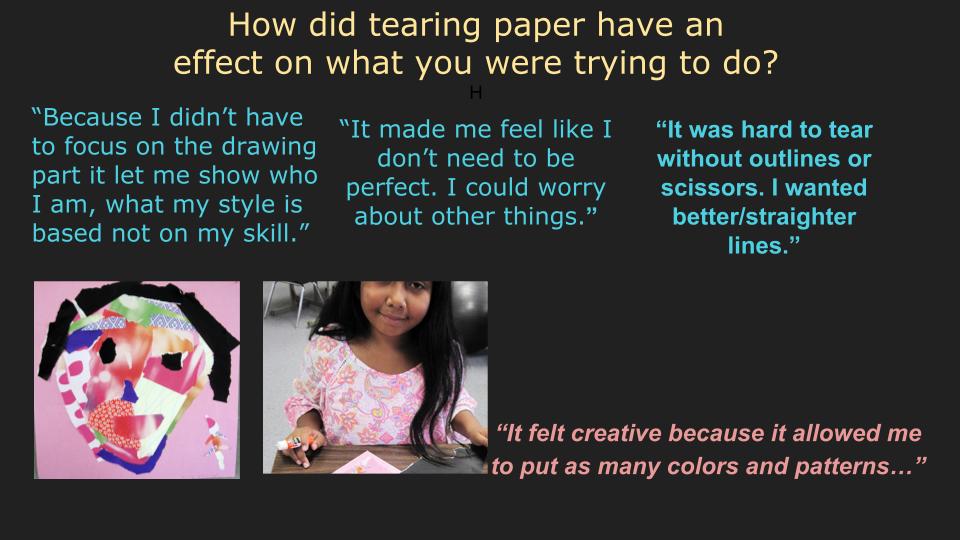

While students work, I move about to encourage and discuss ongoing work. Once students are well into the project I ask each student individually, “What are you thinking about right now?” The simple act of asking what they are thinking midway reminds the student that they are making creative choices and decisions. I take notes and print out and post their quotes with their portraits later. The quotes remind students that there was an active creative process involved and that it remains an important aspect of the piece.

With the portraits posted on the wall, we have a group discussion. Students are asked to notice interesting approaches, things their classmates did that surprised them, and what they can tell about the person in the portrait. It is important to provide an opportunity for students to reflect on visual pieces in front of them and the actual information they convey, as it removes the focus from “Does it look good?” to the thinking behind the pieces.

I also ask about their process – How did the tearing, as opposed to the use of scissors for example, feel and/or change how you approached the project? Students are examining their own process, what challenged or helped them, and how they responded. They gain practice in navigating the ambiguity of open-ended situations and, more importantly, recognizing that they did so successfully.

Reinforcing the creative problem-solving skills in projects, and documenting that process, gives students confidence that thinking and not the “correct” answer is important across the board – in art and elsewhere.

Isn’t that what we all want, students that are thinking?

Dana Squires

Dana Squires has 20 years of experience as an arts integration specialist and teaching artist in Washington State, USA. She has taught in schools at all levels, teaching art, doing collaborative arts integration work, and teacher training. She has worked with refugee organizations, with learners of English as a Second Language, and lived and worked at the village level in both West Africa and Melanesia. Dana studied Making Thinking Visible concepts through The Graduate School of Education at Harvard University.

You can view her work at https://danasquires.com/, and she can be reached at Dana@DanaSquires.com.