Creative Ambiguity

In learning, ambiguity is where the thinking, learning, & creativity, takes place.

By Dana Squires, a teaching artist in Washington State.

“Music is the space between the notes.”

– Claude Debussy

(Birds on a Wire Pierre St John)

The Importance of Ambiguity:

In visual artwork the “empty” space between the primary shapes is called negative space. But this space is actually not at all negative and is the all-important framework for the entire piece. In learning, also, the empty space, or, ambiguity, is where the thinking, the real learning, the creativity, takes place.

I try to include a healthy dose of ambiguity into each and every project.

For many, ambiguity is uncomfortable, even scary. Students can be afraid of not knowing what is expected, doing something wrong or making a mistake. Learning to navigate ambiguity and practice doing so is an important part of learning to learn. Not knowing can be an invitation for creative problem-solving,

How to Include Ambiguity:

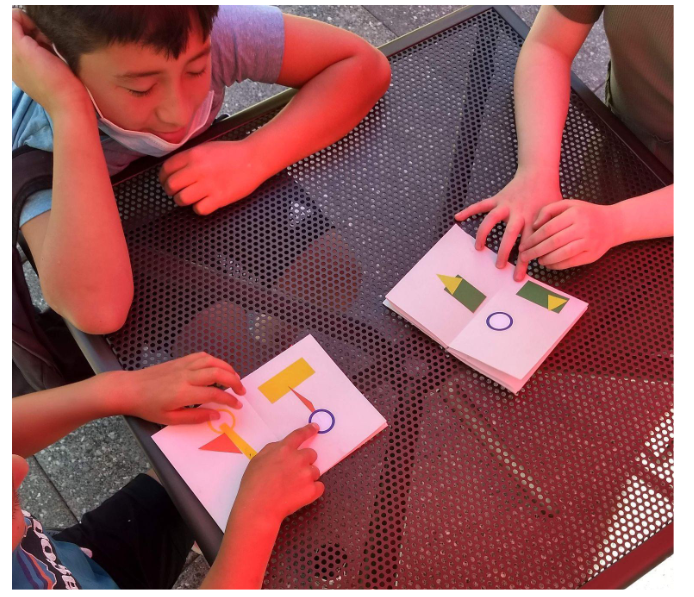

Exercises like these have clear outlines (divide into three groups) but provide freedom for interpretation within those borders (no defined groups.) Students are given the license to interpret the situation in their own unique way and choose how to respond.

Back in the classroom, I ask each student to put their items in order. I let them decide what is meant by “order” without giving examples. The first response is usually the most obvious, and everything is in line by size.

Ask for a third order. Here students begin to get more creative. Things are put in alphabetical order or by “sharpness” or other unique categories emerge.

The point is there are many “orders” in which the objects can be arranged. All of the solutions are “correct.” The students have fun trying to think of creative new orders. I like to document the different groupings in photos for the wall, validating that all solutions were equally valid.

Exercises like these give students practice feeling more confident navigating ambiguous situations. They gain confidence in taking small risks and are prepared to take larger risks in the future.

Students go from “What SHOULD I do?” to “What are the possibilities?”

That is what ambiguity does. It allows possibilities.

Dana Squires

Dana Squires has 20 years of experience as an arts integration specialist and teaching artist in Washington State, USA. She has taught in schools at all levels, teaching art, doing collaborative arts integration work, and teacher training. She has worked with refugee organizations, with learners of English as a Second Language, and lived and worked at the village level in both West Africa and Melanesia. Dana studied Making Thinking Visible concepts through The Graduate School of Education at Harvard University.