Using Artwork to Teach Reading Comprehension Skills:

Why It Works, How It Works

By Trevor Bryan, author of ‘The Art of Comprehension’

Did you know that viewing artwork is a wonderful and efficient way to teach numerous reading comprehension skills?

Well if not, it is.

What’s more is that it doesn’t have to be a long viewing session.

In as little as ten quick minutes, you can begin to help your students to learn to identify key details, synthesize those details into meaning, make inferences, think about themes or big ideas and make meaningful text-to connections.

These are all skills that strong readers develop but they do not have to only be honed with written texts, they can be developed through visual texts too.

This blog post will explain why teaching these skills through visual texts work and show how to do it using examples that can help you get started right away with your students.

Why it works:

Traditional narratives are driven by moods. Read any story, watch any story, listen to any story and one thing you’ll notice is that how the characters feel is front and center. Let’s look at some examples from a few books that show what I mean.

Excerpt from the first Jessica Chapter in Because of Mr. Terupt By Rob Buyea (Yearling, 2010. P. 4).

Act 1, Scene 1

The first day of school. I was nervous. Somewhat. The sweaty-palms-and-dry-mouth syndrome struck. This wasn’t surprising–after all, I was coming to a brand new place. My mom and I had just moved all the way from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean, over here to Connecticut. So it was my first, first day in Snow Hill School.

Mood: Somewhat nervous

And the next two sentences are taken from the second chapter of Wonder by P. J. Palacio (Knopf, 2012, p. 4).

Next week I (Auggie) start fifth grade. Since I’ve never been to a real school before, I am pretty much totally and completely petrified.

Mood: Pretty much totally and completely petrified

In each example above, the mood of the characters have been directly stated by the author. Authors share this information because they know that readers have to know how characters feel in order for the story to make sense. If readers don’t know how a character is feeling (and why they’re feeling that way) the reader will be lost. However, even though knowing how a character is feeling is crucial for comprehending a story, moods aren’t always directly stated. Sometimes, moods in stories have to be inferred and this is where artwork can enter the picture (pun intended) because with artwork, moods also have to be inferred.

In order for students to make inferences, they need to learn to notice key details that provide the clues that can be synthesized into meaning. This is true whether students are working with written texts or visual texts. Somewhat surprisingly, it turns out that the kinds of key details needed to make inferences from any narrative text are the same. This is because there are only a handful of ways that humans can express moods. Once students understand the ways that humans craft moods, they’ll be able to notice these key details in any narrative text that they are working with regardless of its form.

A Tool to Help Students to Notice Key Details:

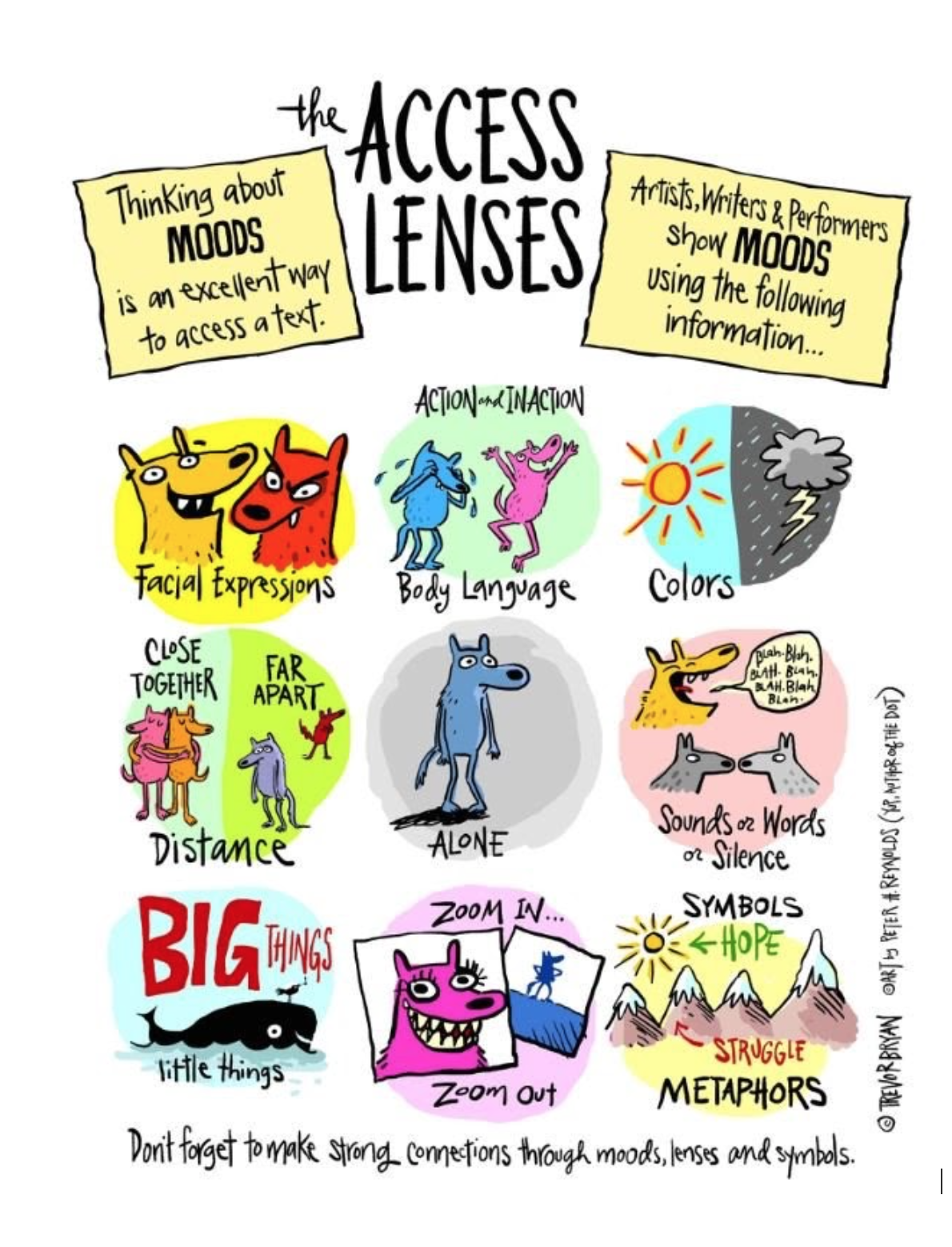

To help students to learn what kinds of key details they need to notice, I developed the Access Lenses which was graciously illustrated by author and illustrator, Peter H. Reynolds (yup, author of The Dot).

The Access Lenses specifically show students what kinds of information to look for in narrative texts that will allow them to make inferences.

Let’s look at three examples so you can start to see how the Access Lenses work.

Example 1:

Here is an example from the picture book, The Kissing Hand by Audrey Penn. This book targets K-2 students. Since the mood in this passage is only shown and not directly stated, it shows us that even young students, who may very well not be able to decode yet, need the ability to infer in order to comprehend stories created specifically for them.

“Chester Racoon stood at the end of the forest and cried.

“I don’t want to go to school,” he told his mother. “I want to stay home with you. I want to play with my friends. And play with my toys. And read my books. And swing on my swing. Please may I stay home with you?”

Mrs. Racoon took Chester by the hand and nuzzled him on the ear.

So what’s Chester’s mood and how do you know?

One way to think about Chester’s mood is through the inaction and action lens: He just stood there (inaction) and cried (action). But with crying we can also imagine the sound lens or even the zoom-in lens (imagining tears streaming down his face). But no matter which lenses we focus on or feel comfortable with, each one helps us to understand that Chester is upset. It may seem simple but audiences have to understand that Chester feels upset in order to comprehend the story. The Access Lenses can help students to root their ideas in concrete evidence from the text.

Example 2:

Now let’s use the Access Lenses to find key details in a visual text to infer how the characters are feeling.

You’ll see that even though the illustration (visual text) is quite simple, several of the Access Lenses have been utilized in order to convey the moods. And because this picture has a strong mood, despite its simplicity, it allows viewers to connect meaningfully to the artwork.

So again, what’s the mood(s) and how do you know?

|

Access Lens |

Group |

Individual |

|

Facial Expressions Lens |

Smiling |

Frowning |

|

Body Language/ Action Lens |

Playing |

Standing |

|

Color Lens |

NA |

NA |

|

Distance Lens |

Close Together |

Far Apart |

|

Alone Lens |

NA |

Alone/Isolated |

|

Sounds/Words/Silence Lens |

Laughing/Screaming/Talking |

Silent/Quiet |

|

Big Things/Little Things |

Big Group/Big Fun |

Feeling small |

|

Zoom-In/Zoom-Out Lens |

Smiles/Ball |

Frown |

|

Symbols/Metaphors |

Ball/Group = Fun/Joy |

Ball/Group = Exclusion |

|

Mood |

Joy, happiness, fun |

Excludes, left out, lonely, sad |

Example 3:

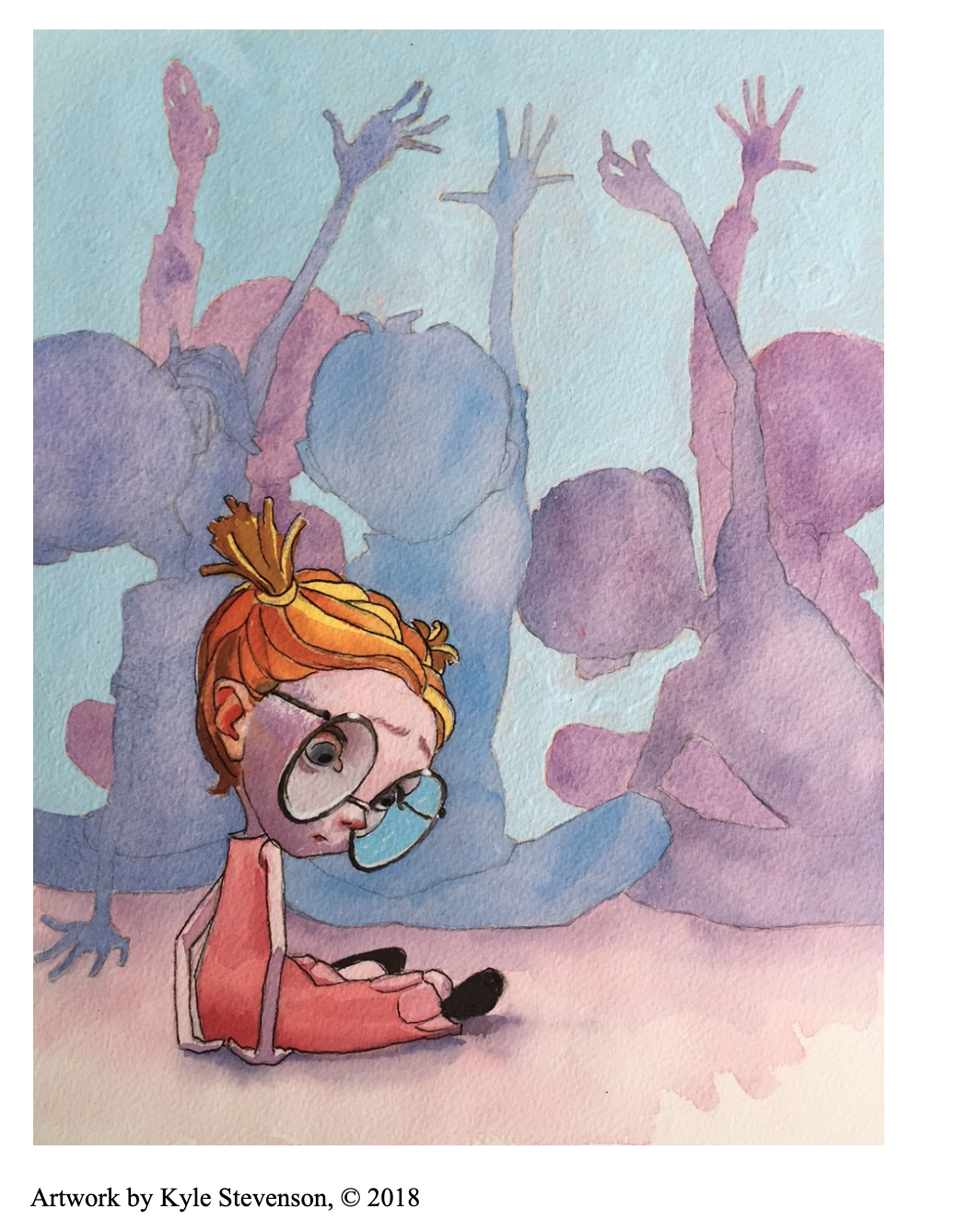

Now let’s look at a more “sophisticated” illustration and see what Access Lenses can be used to make meaning of it (What’s the mood and how do you know?).

|

Access Lens |

Group |

Individual |

|

Facial Expressions Lens |

NA |

Frowning/worried eyebrows |

|

Body Language/ Action Lens |

Hands Raised/Looking forward |

Squished down/sitting on hands/turned away |

|

Color Lens |

Group is all one similar color |

Girl looks more separated because she is a different color |

|

Distance Lens |

Close Together |

Looks separated/feels isolated |

|

Alone Lens |

NA |

Alone/feels alone |

|

Sounds/Words/Silence Lens |

Oo-Oo/I Know |

Silent/Quiet |

|

Big Things/Little Things |

Big Group |

Feeling small |

|

Zoom-In/Zoom-Out Lens |

Arms raised |

Sitting on hands |

|

Symbols/Metaphors |

Group is like a wall |

Carpet time = isolation, embarrassment, discomfort |

|

Mood |

Engaged, included, confident |

Insecure, worried, embarrassed, unsure, upset, isolated |

As you can see, within both of the visual texts, there is a tremendous amount of information provided (text evidence) by the artists to communicate with the intended audience. And also, as with the written texts, what is being communicated is how the characters are feeling (their moods) based on the events that are occurring (the plot).

Having students explore visual texts, whether illustrations or fine artworks, is an excellent and efficient way to help them to notice key details, find textual evidence, synthesize key details into meaning, make inferences, and support their thinking with textual evidence. But this is not all visual texts have to offer. There’s more!

Identifying Symbols

In education, thinking symbolically is often thought of as an advanced skill but in actuality all narratives, whether real or imagined, whether visual or written and despite the age group they are targeting, serve as symbols. It’s the symbolism that makes stories universal. This is why we can read a story about a raccoon character who is nervous to go to school and still relate to the story and still learn from the story.

One way to help students to think symbolically is to teach them that whatever is causing a mood is a symbol of that mood. Because school is making Chester Racoon and Auggie feel nervous or terrified, school is a symbol of discomfort, the unfamiliar or fear. Chester’s mother is a symbol of support and comfort because she starts to make Chester feel better.

When students read books, view narratives or look at isolated pictures, once the mood has been determined using textual evidence (key details), have them think about what is causing the mood. Once students determine the mood and its cause they can make the story or picture bigger by thinking about it symbolically. Determining the mood and it’s cause is where you find the creator’s purpose. Even in abstract artworks that don’t necessarily have any narrative elements, determining the mood and discussing how that mood was crafted through the Access Lenses is a way to help students access the artwork and explore it more deliberately and thoughtfully.

Mood + Cause of Mood = Theme

Beyond thinking about symbolism, determining moods and the cause of the mood is also where you can discover themes. In narratives and in pictures, that which causes or shows the mood is a place where audiences can learn. Take our previous school examples for example. If a character feels uncomfortable because they are doing something they have never done before we can turn that into a theme: When we do unfamiliar things, it can make us feel nervous or scared. This is one lesson from the stories mentioned above. Inevitably, moods in stories change. What causes the character’s mood to change is a major theme of the story. In many cases, that is what the story is about.

Themes can also appear in singular artworks. If we look at the first illustration which shows a character feeling sad because they are not included in the game, we have a theme: When people are left out, it can make them feel sad and lonely. And for the second picture: Not knowing an answer can make us feel isolated or embarrassed or riddled with anxiety.

Finding themes based on moods and their causes is one way that stories and artworks foster social emotional awareness. Stories and artworks are powerful because they can inform and transform lives. When students understand that themes are built around moods and their causes, it makes it more likely that they will be able to craft their own stories and artworks that have clear themes. Helping them learn to put the Access Lenses into their writing and artworks can help them to learn to craft clear moods.

Making Connections

Strong readers also make strong connections. Strong viewers do the same. Identifying moods, their causes, and the symbols of the moods in stories or in artworks can help students to make meaningful connections. Readers and viewers can ask themselves: When have I felt this way? Who or what made me feel this way? When have other characters felt this way? What other paintings have a similar mood? What movies have a similar mood? When did my friends or family feel this way? When could somebody else feel this way? These questions help audiences connect to stories or artworks in sincere ways. They help audiences to use stories and artworks as a springboard to think about their own lives. And they help audiences to develop empathy: a skill that can never be developed enough.

Final Thoughts

You can use the passages and artworks that I shared in this blog to help students get started with exploring visual texts to help them hone their comprehension skills. But most of the books, artworks or animated shorts that you already share with your students can be used too. If or when you use your own texts, take some time with them. Think about how the artists and authors shared and showed moods, what causes those moods, what symbols show up in the story, what themes are there and what connections can you make (what does this story or picture remind you of?). At first, seeing all of these ideas clearly in texts and having meaningful conversations with your students might come slowly but if you give your students a little time and if you give yourself some time, you’ll get the hang of it and the thinking and conversations in your classroom will soar.

Trevor Bryan

Trevor Bryan is an art teacher, author and painter. Trevor has presented at numerous national, state and local art and literacy conferences. He has also worked with several school districts to help them with reading comprehension, writing and arts integration. He is available for virtual and in-person professional development. His book, The Art of Comprehension: Exploring Visual Texts to Foster Comprehension, Conversation and Confidence is available through Stenhouse House Publishers, Amazon, or wherever books are sold.

You can connect with Trevor through Twitter: @trevorabryan, Facebook: Trevor Bryan or The Art of Comprehension or through his Publisher: Stenhouse Publishers