Ink, Press, Inspire

An Educator’s Guide to Relief Printmaking in Pre K-12

Mrs. Hess, St. Francis of Assisi School; Triangle, VA; PreK-8th grade Art;

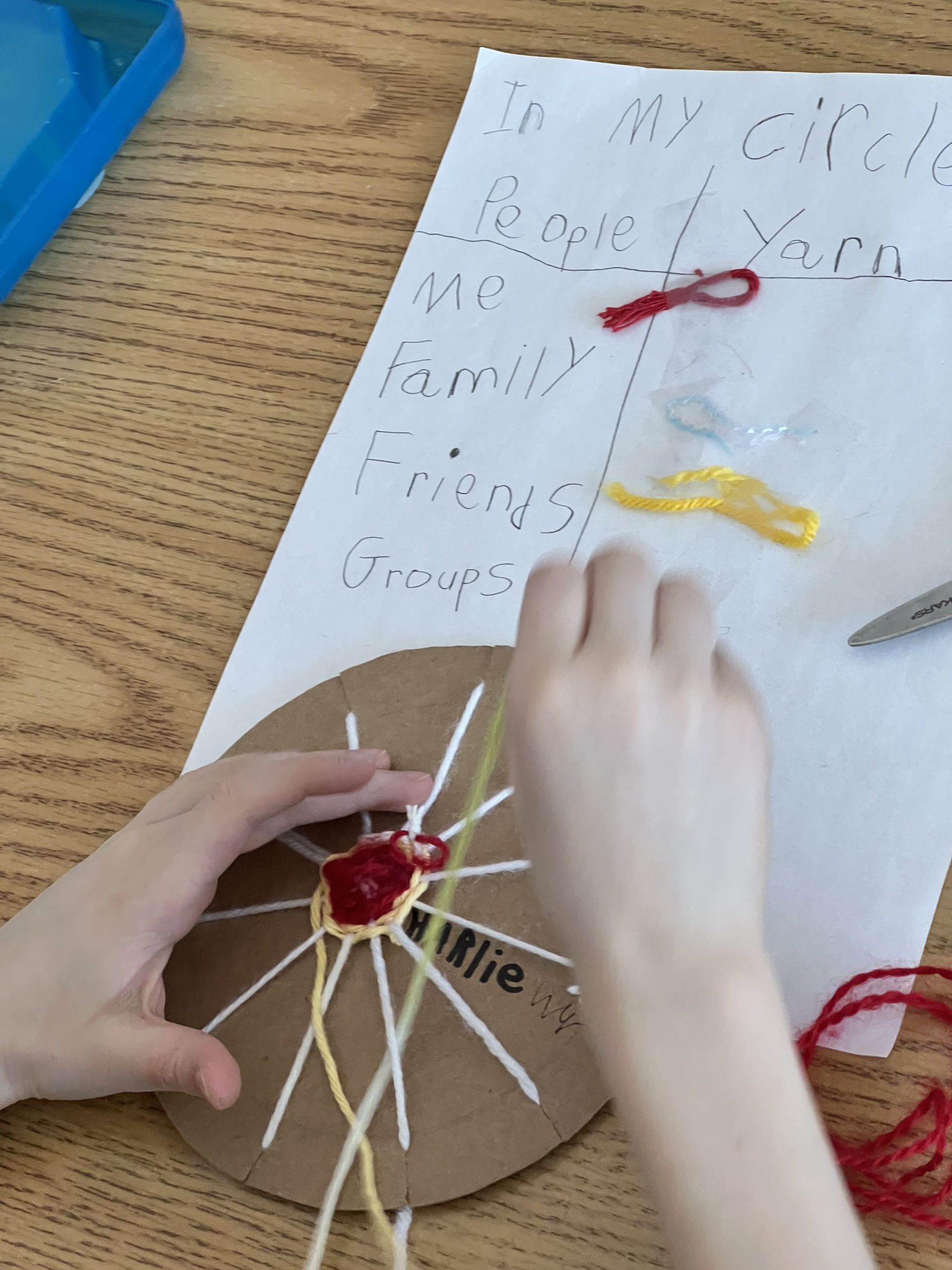

Dr. Debi Bober, Cubberley TK-8, LBUSD, Long Beach, CA, TK-8 Art Specialist;

Mrs. Anderson, Hardin Valley Academy & Knoxville Museum of Art Knoxville, Tennessee; Pre-K-8

Embark on the enriching journey of integrating printmaking into educational settings with our four-part blog series, crafted by four experienced teachers who share their personal journeys and insights.

More About our Expert Contributors:

My name is Linda Hess and I have been an art teacher officially for 10 years. I fell into my job while running a polymer clay after-school program after the former teacher turned in her notice 1 week before school started (yikes!). It was amusing to think I was teaching art since my degree was in Elementary Education, but it ended up being one of the best things I have ever decided to do. I am proud to say that at age 60 I obtained my Master’s degree in Art Education (thank you Art of Education University). Everyone assumed that I had an Arts degree, so I thought it high time to actually get one. I teach PreK-8th grades in a Catholic school in Triangle, Virginia.

My favorite “mantra” to the students is “There are no mistakes in art, only happy accidents” (thank you, Bob Ross) as well as “Your way of creating is the best way. It is YOUR artpiece.” Of course, this has come back to bite me a time or two when my students remind me when redirected, “But Mrs. Hess…”

I have been married for almost 36 years to my high school honey. We have 3 grown children and 2 twin grandbabies (15 months),who thankfully live close enough for a baby fix every couple of weeks.

Hello, fellow Art-involved readers! I’m Shannon Fish, a high school Visual Arts Instructor from Central Ohio, with 20 years of formal public school teaching experience, but nearing 30 years of involvement with teaching in various settings. Prior to being a first year teacher, I made exactly one linoleum print. Ever. One! Initially, I started teaching middle school and was introduced to the idea of printing with styrofoam blocks, and explored with my seventh grade students.

When I arrived at the high school level the concept of teaching printmaking was daunting, and honestly I intended to skip it, until my colleague, Suzy Rogers, taught me the magic of pulling a print! I tell this for two reasons, first to give credit where credit is due, but also to illustrate that anyone can use this exciting medium to expand the horizons of their students—just give it a try! You’re here reading this blog post, so you’re already well on the way!

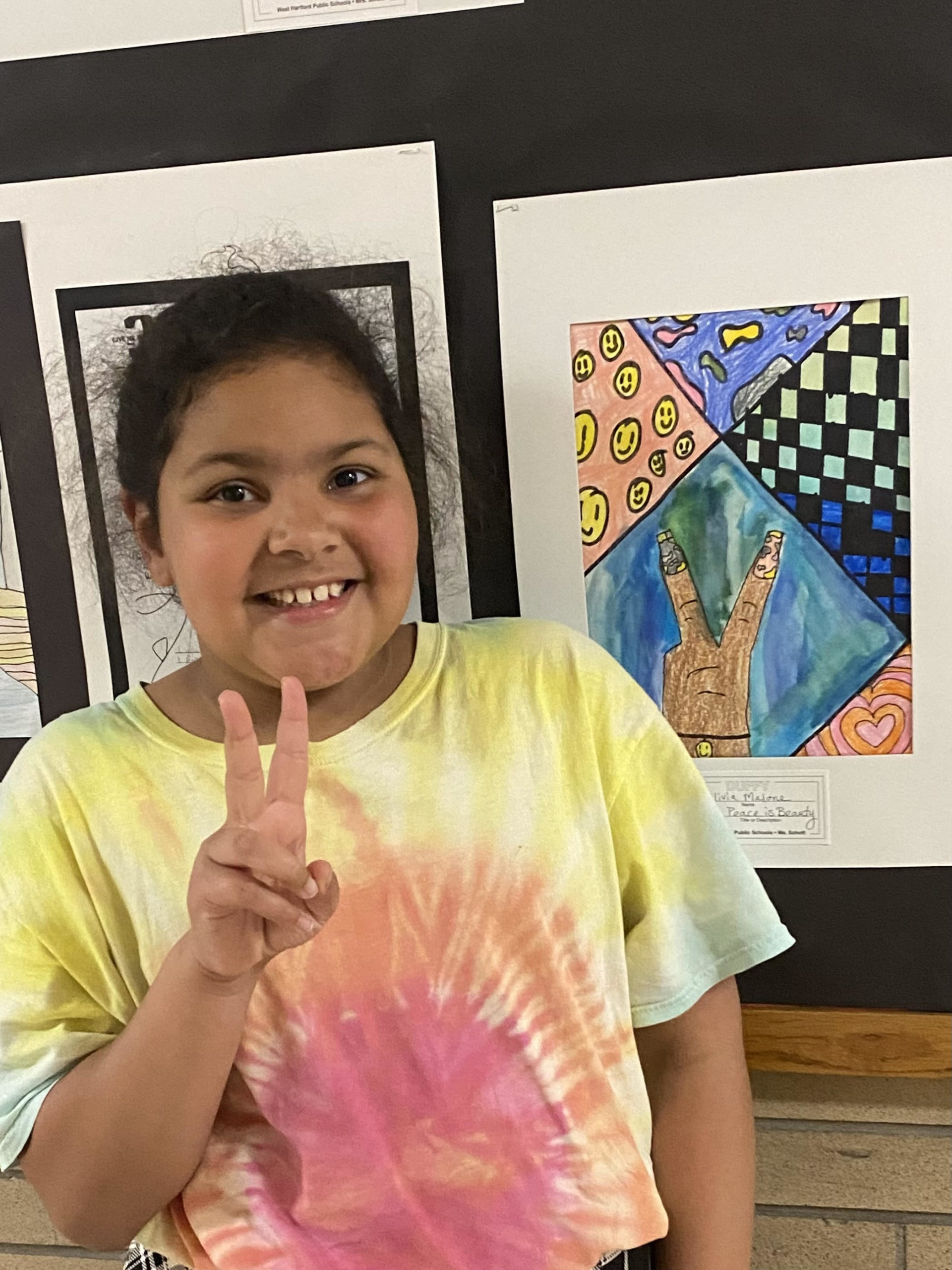

This has been the best year of my career! When Proposition 28, the Arts and Music in School Initiative, passed in California in 2022, my school district jumped on hiring new art teachers to fill our elementary schools. I had been teaching for 29 years, and have taught each grade from Kindergarten through eighth grade during my career, so when the opportunity to teach art to ALL grades at my K-8 school came about, I was ecstatic. The arts have always been my passion, from my start at Orange County High School of the Arts, Idyllwild Arts Academy, and then Chapman University for music. I dabbled in various art and music classes through high school and college, not knowing exactly what direction my life would take me. I came to the realization that, as a teacher, I could share my passion for art and music with thousands of students. Over my career, I’ve realized the value of visualizing when thinking, presenting ideas creatively, and translating learning into songs, dances, raps, and artwork. I use chants, hand movements, music, and digitally animated visuals during instruction because when multiple modes of learning are accessed simultaneously, student learning occurs more deeply. This focus on effective teaching has brought me many achievements, including the dissertation award at UCLA for my research in interactive instruction in high poverty classrooms. In 2019, I was awarded Los Angeles County Teacher of the Year and a finalist in California Teacher of the Year, out of 180,000 teachers. Now, in my thirtieth year of teaching and thanks to funding from Prop 28, I am the new art teacher at Cubberley TK-8 in Long Beach, California.

My name is Donna Anderson. I’m the author of Experience Printmaking, a textbook which is part of the Studio Series from Davis Publications. I taught Visual Art in Knoxville, Tennessee for 40 years and am now retired. Presently, I am working on the second edition of my book which will also be published in a digital format. Although retired, I taught and still teach at the Knoxville Museum of Art’s Summer Art Academy. Funnily enough, in my last year teaching high school before I retired, there were eight seniors in my Printmaking class who had art camp with me as a five-year-old! Although they weren’t planning to go into art-related majors in college, they still loved art and continued to learn new techniques and produce artwork. Isn’t this what you want?